A Prophetic Vision in a Polish Arcadia of Temple of the Sibyl

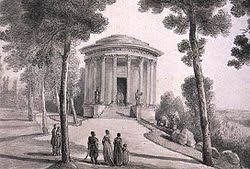

Nestled within the breathtaking landscape of the Pulawy parklands, amidst meandering paths and serene ponds, stands a building of profound symbolic power and unparalleled historical significance: the Temple of the Sibyl. This elegant neoclassical rotunda, perched romantically on a bluff overlooking the Vistula River, is far more than a mere garden folly; it was conceived as a sacred secular sanctuary, a “Temple of Memory” designed to safeguard the soul of a nation that was being systematically erased from the map of Europe. Its construction was the visionary project of Princess Izabela Czartoryska, a matriarch of one of Poland’s most powerful aristocratic families, in the aftermath of the devastating partitions of Poland-Lithuania. As foreign powers—Russia, Prussia, and Austria—dismantled the Polish state in the late 18th century, Princess Izabela embarked on a courageous and patriotic mission to preserve Polish cultural heritage for future generations. The temple, inspired by the ancient Roman Temple of Vesta in Tivoli and the mythical prophetic Sibyls of antiquity, was intended to be a beacon of hope, a place where the relics of Poland’s glorious past would be kept safe until the nation could one day rise again, prophesying a future resurrection through its very existence and the treasures it guarded within its hallowed walls.

Izabela Czartoryska The Sibyl of Pulawy

To understand the temple, one must first understand the extraordinary woman who willed it into being. Princess Izabela Czartoryska was a figure of the European Enlightenment—a prolific writer, art collector, landscape designer, and a fierce patriot. Following the trauma of the Kosciuszko Uprising (1794) and the subsequent Third Partition (1795), which ended Polish sovereignty, her estate in Pulawy became the unofficial spiritual and cultural capital of the absent nation. She was deeply influenced by her travels across Europe, particularly by the romantic and symbolic landscapes of England. The idea for the Temple of the Sibyl came to her as a direct response to national tragedy. She herself became the modern Sibyl, not foretelling the future, but actively shaping it through cultural preservation. A little-known story reveals her meticulousness; she personally oversaw the design and construction, demanding inscriptions be carved into the frieze that read “The Past to the Future”, and she meticulously curated every item placed inside, often writing the descriptive labels herself. Her salons in Pulawy were also a hotbed of political intrigue, where plans for the future restoration of Poland were whispered among the intellectual elite, all under the watchful and often hostile eyes of Russian authorities, making the temple a daring act of cultural defiance.

Architecture as Symbolism A Modern Oracle

Designed by the Polish architect Chrystian Piotr Aigner and completed in 1801, the temple’s architecture is a masterclass in symbolic neoclassicism. The choice of a circular form, evoking the ancient Roman temples dedicated to Vesta, goddess of the hearth and home, was deeply intentional. It symbolized the eternal and cyclical nature of history and hope, suggesting that just as Poland had fallen, it would inevitably rise again. The simple, elegant Doric columns support a frieze inscribed with its powerful motto, while the building is crowned with a dome, representing the vault of heaven under which the Polish nation endured. The interior was deliberately designed to feel like a sacred space, dimly lit and hushed, with a central oculus allowing a single shaft of light to illuminate the relics below, creating a reverential atmosphere. The building was not meant to be a palace or a showroom but a shrine, a secular ark for a national covenant. Its location within the park was also carefully chosen; it was placed on a site previously occupied by a fortress-like manor, symbolically replacing a structure of war with one of culture and memory, a powerful metaphor for the princess’s belief in the ultimate triumph of cultural resilience over military conquest.

The Sacred Relics: A Collection of National Mystique

The original contents of the Temple of the Sibyl formed what is considered Poland’s first-ever national museum, a collection of priceless historical artifacts that were transformed into holy relics of secular patriotism. Princess Izabela traveled across Europe, often at great personal risk and expense, to acquire objects connected to Poland’s kings and national heroes. The collection was breathtaking in its symbolic weight: it included the sword of King Sigismund I the Old, the ornate goblet of King Jan III Sobieski commemorating his victory at the Battle of Vienna, and personal effects of national martyrs like Tadeusz Kosciuszko. Perhaps the most emotionally charged items were the simple, soil-stained spurs of Prince Józef Poniatowski, who drowned during the Battle of Leipzig. However, a lesser-known and deeply poignant part of the collection were what she called “national souvenirs”—fragments of the coffin of Poland’s greatest poet, Jan Kochanowski; a piece of the throne of King Stanislaw August; and even soil from the battlefield where Kosciuszko fell. These fragments, seemingly insignificant to an outsider, were imbued with immense power as tangible connections to a lost world, making the temple a truly unique and innovative concept in museology, where emotional and national value far exceeded any mere monetary worth.

The Hidden Chamber and the Russian Response

As Russian surveillance and repression intensified after the November Uprising of 1830, the Czartoryski family was forced into exile, and Pulawy was confiscated by the Tsarist authorities. Facing this imminent threat, the curators of the collection performed a daring and secret act of preservation. The most priceless treasures from the Temple of the Sibyl, along with those from the nearby Gothic House, were hastily smuggled out of Pulawy and hidden. Family lore tells of a secret vault or a buried cache somewhere on the vast estate, though the exact location was known to only a trusted few and has since been lost to time. The majority of the collection was successfully transported to the Czartoryski family seat in Paris, the Hôtel Lambert, and later, in 1876, to Kraków, where it forms the core of the renowned Czartoryski Museum, home to Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine.” The original temple in Pulawy was stripped of its treasures by the Russians, who understood its power as a symbol of Polish nationhood and sought to neutralize it. They transformed the building, once a sanctuary of memory, into a storage shed and later an archival office, a deliberate act of desecration meant to erase its patriotic meaning and reduce it to a purely utilitarian structure.

The Temple of the Sibyl of 20th Century

The Temple of the Sibyl’s journey through the 20th century mirrored that of Poland itself—periods of rebirth, devastation, and eventual restoration. Following World War I and the restoration of Polish independence, the temple was recognized as a national monument and efforts began to restore its dignity. However, World War II brought new horrors; the Nazi occupation saw the park and buildings used for various military purposes. In a little-documented episode, there are suggestions that German officers, aware of the legend of hidden treasures, may have conducted their own unofficial searches of the grounds, though nothing was ever confirmed to have been found. The post-war communist era was another challenging period; the state was ambivalent about celebrating the legacy of the aristocratic Czartoryskis, yet the temple’s status as a monument of national culture ensured its survival. It was not until after the fall of communism in 1989 that a full and comprehensive restoration could begin. Today, the temple has been lovingly returned to its former neoclassical glory and serves as a museum once more, housing exhibits on the history of the Czartoryski family and their immense contribution to Polish culture, though the original core collection remains proudly in Kraków.

The Temple of the Sibyl Enduring Power of a Symbol

The Temple of the Sibyl today is a place of pilgrimage for those interested in Polish history and the powerful idea of cultural resilience. It stands as a testament to the revolutionary idea that a nation’s identity is not defined solely by its borders or government, but by its culture, history, and memory. The story of the temple is a narrative about the power of women in history, often overlooked, with Princess Izabela’s vision and determination saving countless artifacts that would have otherwise been lost. It is also a story about the museum as a concept, born not from imperial plunder but from a need for preservation in the face of existential threat. Visitors walking through the park in Pulawy experience a landscape designed to inspire reflection on nature, history, and art. The Temple of the Sibyl remains the philosophical and emotional heart of this design, a beautiful and melancholic symbol of loss, but more importantly, of unwavering hope. It is a building that prophesied a future it helped to create, proving that the most powerful forces in history are not always armies and treaties, but sometimes the simple, enduring act of remembering.

Go to main page