A Accidental Discovery in the Stone Quarry

Tucked deep within the Snieznik Massif of the Sudetes Mountains in Lower Silesia, Poland, lies one of Europe’s most magnificent and scientifically significant subterranean realms: the Bear Cave, or Jaskinia Niedzwiedzia. This sprawling karst labyrinth, adorned with a breathtaking array of calcite formations and holding within its silent chambers the bones of Ice Age giants, was not discovered through purposeful exploration but was instead revealed entirely by accident, a secret unearthed by the relentless march of industry. In October 1966, workers at a marble quarry in the small village of Kletno were conducting a routine blast to expose new veins of rock when the explosion tore away a mountainside face, revealing a dark, gaping void that had been sealed for millennia. The first workers to peer inside were met not with a simple fissure, but with the staggering sight of a massive bone pile, a tangled ossuary dominated by immense skulls and vertebrae that could only belong to a creature of mythic proportions. This initial, shocking discovery immediately halted quarrying operations and triggered a frantic call to archaeologists and paleontologists from Wroclaw University, who descended upon the site to confirm the unbelievable: the workers had inadvertently blown open the door to an extensive cave system that had served as the final resting place for hundreds of cave bears, a pristine time capsule from the Pleistocene epoch that had been perfectly preserved in the cold, stable climate behind its sealed entrance, waiting for a dynamite blast to announce its existence to the modern world.

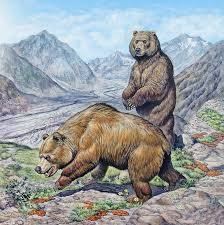

The Pleistocene Graveyard of Bear Cave Giants

The most defining and awe-inspiring feature of the Bear Cave, and the source of its name, is the unimaginable quantity of prehistoric fauna remains found within its deepest chambers. The cave was not a mere occasional den but a massive trap and a natural cemetery for the mighty Ursus spelaeus, the cave bear, a massive herbivorous relative of the modern brown bear that could weigh over one ton and stand over three meters tall on its hind legs. Generations of these bears hibernated in the cave over tens of thousands of years, and many individuals, particularly young, old, or sick ones, never awoke, their remains accumulating on the cave floor. However, the cave’s fossil record extends far beyond bears, painting a vibrant picture of the Ice Age ecosystem. Paleontologists have meticulously excavated the bones of over fifty different species, including wolves, lynxes, foxes, and immense numbers of smaller mammals like rodents and bats. The most thrilling and rare discoveries have been the remains of Ice Age predators like the cave lion and the relentless wolverine, creatures that likely entered the cave to scavenge the bear carcasses and themselves became trapped. The sheer density of bones is unparalleled in this part of Europe; in some sections, the fossil layer is over several meters thick, representing a continuous record of life and death spanning thousands of years, a natural archive that has provided scientists with an unprecedented window into a lost world and the climatic shifts that eventually led to the extinction of its most iconic megafauna.

The Cathedral of Bear Cave Calcite

While the bones provide a direct link to the past, the cave’s enduring beauty lies in its spectacular and actively growing speleothems—the formations created by the slow, patient drip of mineral-rich water. The Bear Cave is renowned for possessing some of the most diverse and pristine calcite decorations in all of Poland, a dazzling underground gallery sculpted by nature over hundreds of thousands of years. The chambers are adorned with a breathtaking variety of formations: delicate, needle-like stalactites hang from the ceilings like frozen chandeliers, while robust stalagmites rise from the floor to meet them, some having fused into massive columns that appear to support the very weight of the mountain. The cave’s unique microclimate, characterized by near-100% humidity and a constant, cool temperature, has allowed for the creation of exquisite and more rare formations like flowstones that resemble frozen waterfalls, intricate helicities that twist and curl in seemingly impossible defiance of gravity, and delicate, crystalline clusters of cave coral that encrust the walls. The crown jewel of the system is the majestic “Palm Tree,” a towering, multi-faceted stalagmite that is one of the largest of its kind in Poland. This ongoing geological artistry, where a single drop of water can take over a century to deposit a mere cubic centimeter of calcite, transforms the cave from a simple geological formation into a living, breathing underground cathedral, whose beauty is both timeless and continually evolving.

A Labyrinth of Three Levels and Hidden Rivers

The Bear Cave is not a single, simple tunnel but a complex, multi-level hydrological system that continues to challenge and fascinate speleologists. The explored part of the cave, which stretches for over 4.5 kilometers, is divided into three distinct tiers, each telling a different part of the cave’s geological history. The upper and middle levels, which are open to tourists, are largely fossilized, meaning the water that created them has found new paths deeper down, leaving these passages dry and safe for exploration. The lowest level, however, remains an active water corridor, where an underground river still flows, carving new passages and continuing the slow work of dissolving the marble rock. This river is the true architect of the cave, and its inaccessible passages are believed to extend for many more kilometers, connecting to a vast and unexplored network deep within the mountain. The cave’s climate is meticulously controlled by this hidden hydrology and by a unique ventilation system known as “cave breathing,” where air pressure differences between the entrance and other fissures cause the cave to literally inhale and exhale, maintaining a constant temperature of around 6°C and preserving the delicate balance necessary for both the preservation of the ancient bones and the growth of the fragile calcite formations. This complex, three-dimensional structure makes the Bear Cave one of the most sophisticated and dynamic cave systems in Central Europe.

The Delicate Art of Preservation and Tourism

Opening such a fragile and scientifically priceless environment to the public presented an immense challenge that required pioneering solutions in conservation and sustainable tourism. From the very beginning, the primary goal was to protect the cave’s ecosystem from the damaging effects of human presence—body heat, exhaled carbon dioxide, lint, and microorganisms can all disrupt the microclimate, halt calcite growth, and promote the destructive growth of algae and mosses known as “lampenflora.” To mitigate this, the tourist route was carefully designed on elevated metal walkways and staircases that minimize contact with the cave floor and walls. A sophisticated two-door airlock system was installed at the entrance to prevent the exchange of air with the outside environment. Perhaps most importantly, the number of daily visitors is strictly limited and regulated through a timed ticket system, and the interior is lit by cold LED lighting that produces minimal heat. The management of the cave is a constant balancing act between allowing public access to this natural wonder and fulfilling the paramount duty to preserve it in as pristine a state as possible for future scientific study and for the generations of visitors yet to come, ensuring that the accidental discovery in the quarry continues to inspire awe without being loved to death.

The Unfinished Map: Ongoing Exploration

A common misconception is that the Bear Cave has been fully explored and mapped. In reality, speleological work is ongoing, and the cave continues to reveal new secrets. The breakthrough in 1966 was only the beginning. Intensive exploration in the following decades, often involving difficult and dangerous squeezes through flooded sumps and narrow fissures, led to the discovery of the extensive middle and lower levels. Each new expedition has the potential to extend the known length of the cave or discover new, magnificent chambers sealed off for millennia. The most significant recent discovery occurred in 2015, when a team exploring the lowest, flooded levels found a new branch subsequently named the “Passage of the Year 2015,” which contained stunning, untouched formations and new fossil deposits. This ongoing exploration requires a combination of diving expertise, climbing skill, and geological knowledge, as teams navigate the active underground river and unstable rockfalls. The continued discovery of new passages proves that the Bear Cave is not a static museum exhibit but a dynamic, living geological entity, much of which remains uncharted territory, holding the promise of further breathtaking finds that could deepen our understanding of the region’s geological and paleontological history.

A Portal to a Lost World of Bear Cave

The Bear Cave in Kletno is far more than a tourist attraction; it is a multi-layered repository of natural history, a place where geology, paleontology, and climatology intersect in a single, awe-inspiring location. It offers a incredibly rare and tangible connection to the Ice Age, allowing visitors to walk through the very dens of extinct giants and see their bones exactly where they fell tens of thousands of years ago. Simultaneously, it showcases the patient, beautiful work of geological forces that continue to shape the world beneath our feet. The cave’s story—from its accidental discovery and the sacrifice of the quarry to the ongoing efforts to preserve its delicate environment—is a powerful narrative about our relationship with the natural world. It represents a shift from resource extraction to conservation and reverence. A visit to the Bear Cave is a humbling journey back in time, an opportunity to stand in a silent, majestic hall of stone and bone and contemplate the deep time of the Earth, the creatures that once roamed the land above, and the invisible, persistent drip of water that is still building a hidden masterpiece deep within the mountains of Silesia.

Go to main page